Experiential Report

The experiences of our trip to Iran, a country completely unknown to me previously, lie, in this moment where I’m writing this text, quite some time ago in the past. Nevertheless, they continue not only to resonate – they keep changing and evolving as time passes. A shift in perspective.

My investigations in the residency were primarily devoted to spatial lines of inquiry: questions that were addressed in particular to the psychological quality of architectonic, urban planning and social spaces, and how one moves through these spaces. For what quickly became apparent to me was a certain difference, an otherness, something unfamiliar in the familiar. And this unfamiliar part struck me first off in how space is organised. Private and public spaces are structured in an almost diametrically opposite fashion, and yet they constantly overlap. With the caesura of the Islamic Revolution, these spaces were separated to the greatest possible extent: private life continued, now behind closed curtains. The curtains in my room were even installed in such a way that one couldn’t even open them. During the day, shops put up their roller blinds. Then, as if a wall is missing, they stand completely open towards the street side, defenceless. At night, everything is closed up and locked, (almost) none of the shop windows hint at what lies hidden behind the blinds. There is a vibrant retail sector, with small businesses, associations of individual merchants of the same products can be found grouped together, stretching out for whole blocks. The famous Grand Bazaar is akin to a city within the city. Various levels, branches and shops are nested within one another. Occasionally, I lost my bearings so completely here that I no longer had the slightest clue whether I was in a shop or on the street. In my encounters during these strolls, the people of Teheran were always incredibly open, curious and willing to help. Although we didn’t share a common language, we always managed to communicate. Mehdi, our wonderful guide and mentor to the group, once described Iran to me as a sort of “gate”: a transit zone, a point of accumulation for trade, politics and religion between the surrounding neighbouring countries, since time immemorial.

One day, while occupied with questions regarding the intersection of public and private spaces, together with a friend, Afsun Moshiry, I went to various construction sites in the city and investigated the working methods of the crews with her there, composed primarily of guest workers from Afghanistan. What was very interesting is that these workers, most of them illegally employed, move from one construction site to the next, like nomads. Their private lives play out exclusively at these construction sites. With a fair bit of persuasion and curiosity, we were able to speak to a couple of them, who then invited us spontaneously into their (clandestine) living quarters and bedrooms. From pinned-up love letters and painted symbols on the walls with a gilded appearance, improvised living room furnishings made of building materials to peepholes facing the street, here we discovered a whole universe of an invisible living environment in the middle of a construction site.

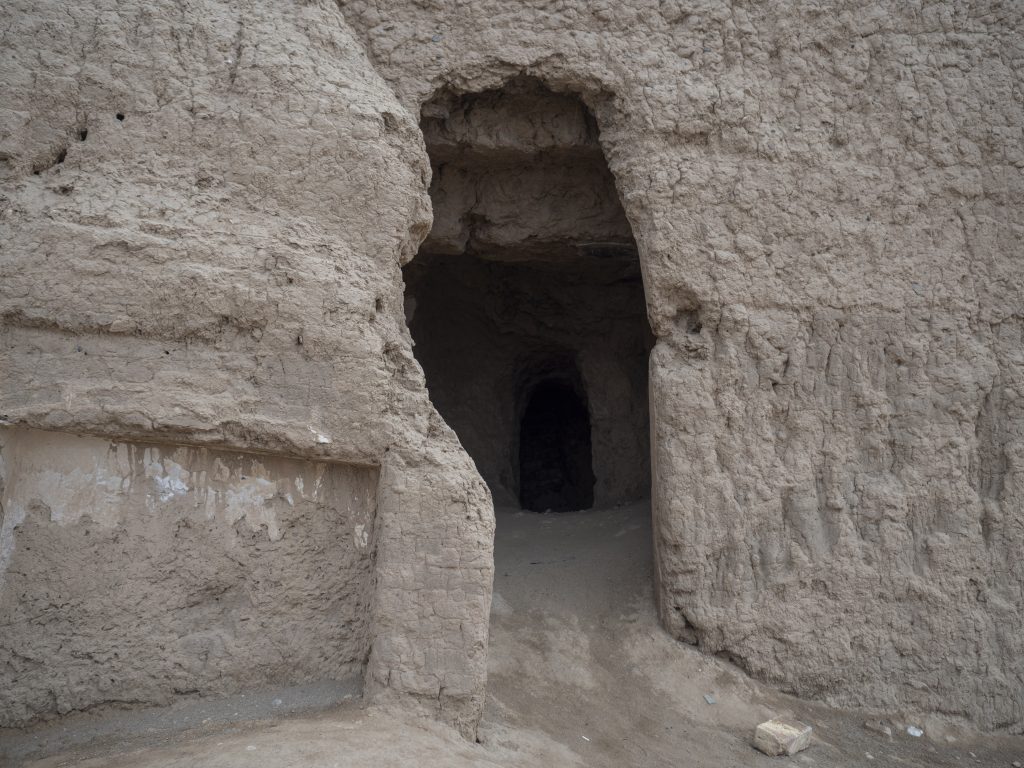

Another visit, this time to the desert city of Nushabad in the Isfahan region, has also remained particularly etched in my memory. Only recently, in 2006, a tunnel system with an area of 4 square kilometres was discovered beneath the city: a further, hidden city composed of three layers on top of each other, featuring ventilation shafts, secret passageways, traps, escape routes and chambers, where all aspects of village life could continue during states of emergency. The construction of this old city, built around 1500, most likely took place “invisibly”: the clay removed in building the tunnels and chambers was made immediately available for the construction of above-ground buildings. This approach ensured that the work on the bunker system left no visible traces.

Work description

A Temporary Installation in the Living Quarters of the “Kooshk” Residency

For the conclusion of our residency at Kooshk, we, four artists, carried out sonic actions in various parts of the city and invited the public to attend an “open studio” session. At the beginning of our time in Teheran, we were quickly faced with the question of how and where we could work. The familiar setting of a studio equipped with various tools was absent – so I decided to use the living quarters of the residency space as a place for work and presentation. To this ends, I selected three specific places within the house. Since it was a private space, I was not permitted to announce the location publicly. As a result, we invited friends of friends through word-of-mouth.

Oliver

The guests were received in the living room, cakes and tea were served, in accordance with typical Iranian hospitality. An hour-long video of Oliver, the house tomcat, played on the large flat-screen monitor that was otherwise a part of the normal furnishings. One could see the cat, how he ambles with curiosity through my room on various evenings, exploring the permanent changes from day to day with alert interest. Aside from the cat, the video shows my living situation, with my private objects in the sleeping room I have transformed into an atelier. Oliver used to be a stray cat, before deciding on his own will to reside at Kooshk. When he moved in, however, our hosts became worried that he was in danger on the street, and so he was no longer allowed to leave the residency. Which of course didn’t keep the clever tomcat with the help of his friends, who call for him mournfully at night, from one day finding an exit via the roof in the courtyard and a gap in the four-metre-high fence, in order to pursue his nightly forays. Of course, he never failed to return.

An Experiment

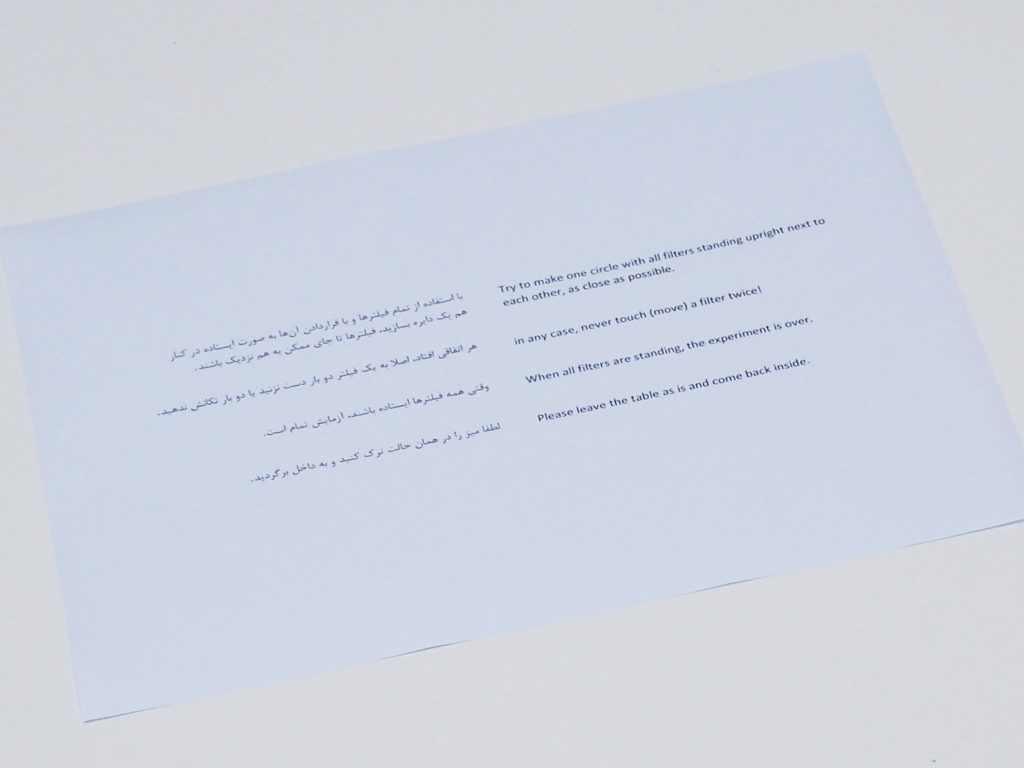

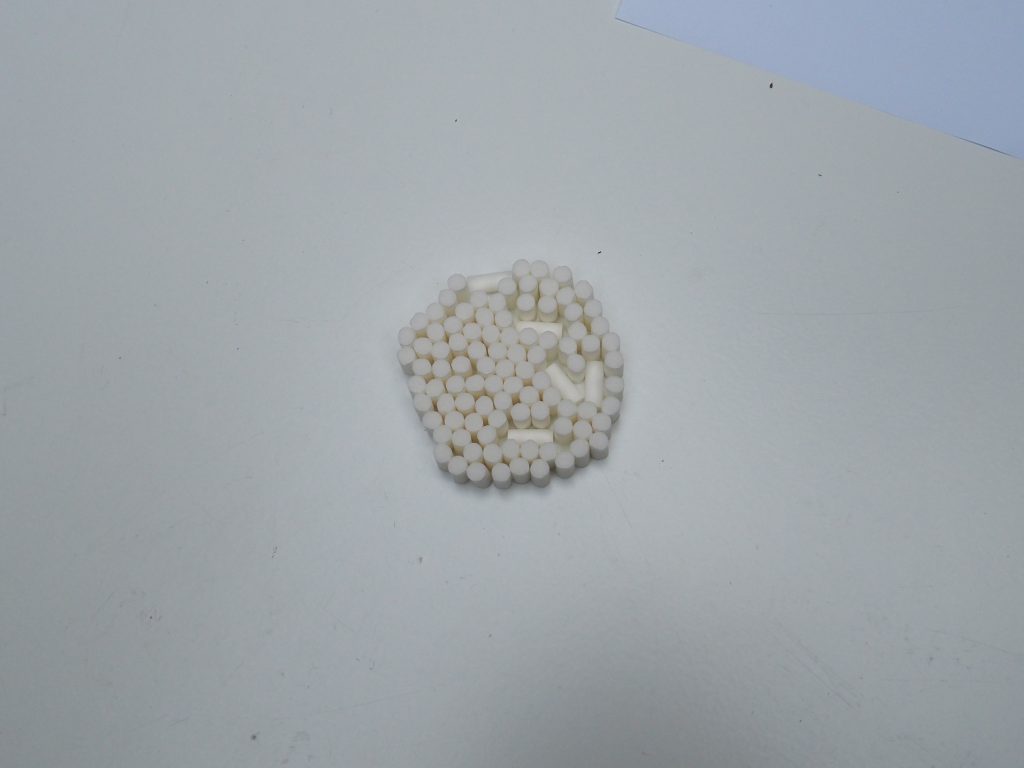

From the living room, I asked two guests at a time to accompany me into the courtyard, to take part in a little experiment. Two tables with two chairs, backs facing one another, stood at the end of the house’s own courtyard, one in each of the two corners. I lowered the fabric-covered canopy at these points, in order to separate the working areas from the rest of the courtyard and at the same time reveal the sky above the tables. On each table lay a pile of 100 cigarette filters with the following task, translated into Farsi and English: “Try to make one circle, with all filters standing upright next to each other. In any case, never touch or move a filter twice. When all filters are standing, the experiment is over. Please leave the table as is, and come back inside.”

The Room

As soon as the guests came back into the house, I brought them into my sleeping room via the stairs and led the next two participants into the courtyard. The furnishings of my room were taken apart to the largest extent possible without using tools. A reversible shift of the interior: stripped of their function and exposed as material, the furniture elements were reassembled in a new way. The result was a miniature backdrop of a city-like landscape, inhabited by two wooden figures, which were originally curtain rods. The constructions were laid out according to strict vertical and horizontal axes and were under material tension, or merely balanced. A tower made of the wood side panels of the beds, two drawers and blankets was held in place exclusively through the power of the squashed lining. At the end of the room, one could make one’s way out onto the balcony and to the headboards leaned against the railing. The view looked out over the courtyard, hung with fabric. One could see the two gaps where the canopy was opened for the experiment, and watch the city’s horizon above the high fence made of wood slats lined up in a row.